Ancient Kingdom of Lydia Has Re-Appeared to Haunt Armenia

BY STEPHAN AMATUNI

Lydian International and its Armenian subsidiary are making national headlines in Armenia regarding the highly controversial Amulsar gold mine, which is expected to resume operations after the government indicated it is giving a green light for the project.

However, hundreds if not thousands of environmentalists and others are protesting the move, arguing that it will destroy natural resources and contaminate waters, particularly the Jermuk springs and Lake Sevan.

The fact that Lydian International is registered in the tax-haven of Jersey makes opponents of the project wonder who the real shadowy owner of the company is.

But why is the company called Lydian anyway?

One can assume that the owner or owners of the company got their inspiration from the Iron Age Kingdom of Lydia of western Asia Minor, located east of ancient Ionia in the modern western Turkish provinces of Uşak, Manisa and inland İzmir.

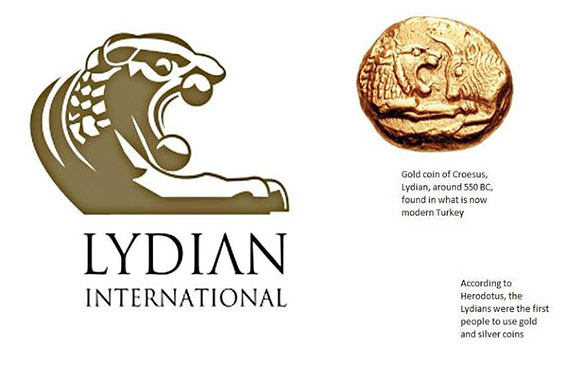

Its logo depicting a lion is the very same lion which is depicted on the famous gold coin of Croesus, the last and most notable king of Lydia. The Lydians were the first to have invented gold coins, according to ancient accounts. Gold from the mines and from the sands of the River Pactolus filled Croesus’ coffers to overflowing.

In Greek and Persian cultures the name of Croesus became a synonym for a wealthy man. He inherited great wealth from his father who had become associated with the Midas mythology, because Lydian precious metals came from the river Pactolus in which King Midas supposedly washed away his ability to turn all he touched into gold.

Croesus’ wealth was in fact so vast that modern day expressions such as “rich as Croesus” or “richer than Croesus” are used to indicate great wealth.

Croesus Treasure aka Karun Treasure

Karun Treasure is the name given to a collection of 363 valuable Lydian artifacts dating from the 7th century BC and originating from Uşak Province in western Turkey, which were the subject of a legal battle between Turkey and New York Metropolitan Museum of Art between 1987 to 1993, and which were returned to Turkey in 1993 after the Museum admitted it had known the objects were stolen when they had purchased them. The collection is alternatively known as the Lydian Hoard.

The curse of the treasure has its origins in 1965, when it was discovered in the village of Güre in the western province of Uşak, Turkey by five villagers who illegally dug up the tumulus of a princess from Lydian times and stole the jewelry that had been buried with her. A year later, villagers robbed the rest of the treasures.

In the 1970s, Boston Globe journalist Robert Taylor and one of the directors at a museum in Boston, Emily Vermeule, had alleged that 219 pieces of Lydian artifacts had been purchased by the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art between 1966 and 1968.

A Turkish journalist, Özgen Acar, who was aware of the situation, happened to see 55 pieces of the Lydian Hoard on display at the museum in New York while he was visiting in 1985 and went on to discover that the rest of the treasure was also being stored there. The Metropolitan Museum or Art described the artifacts as being of Greek origin, which according to Acar and officials at the Uşak Museum, was done with the intent of covering up the actual location of the discovery.

The journalist immediately notified Turkish officials, who started a legal process to take back the artifacts in 1987, just three days before New York Metropolitan Museum of Art would have become the rightful owners of the treasure.

Following a six-year legal battle, the museum agreed that they had known the artifacts had been stolen when they purchased them, and a U.S. federal court in New York decided to return the artifacts back to Turkey.

The collection made sensational news once again in May 2006, when a key piece on display in Uşak Museum, along with the rest of the collection, was discovered to have been switched with a fake.

People in Uşak believe that this treasure is cursed and that it brings nothing but misfortune and death.

Popular rumor has it that all seven men involved in the 1965 illegal digs of the burial mounds in Turkey died violent deaths or suffered great misfortune, according to The Guardian.

Villagers from Uşak told one reporter that one of the thieves had lost three of his sons, one of whom was gruesomely murdered, with his throat slit. His other sons died in two separate traffic accidents, and in different countries. The thief was later paralyzed, and later died.

Another went through a bitter divorce that was followed by the death of his son, who committed suicide.

Bayırlar, who sold the artifacts overseas, was also alleged to have gone through terrible times in his life and died in pain. (Source, Today’s Zaman [September 25, 2011])

Currently, the mysterious artifacts are exhibited in the Uşak Museum of Archaeology.

Even if Lydian International has found its inspiration from the story of the wealthy Lydian king and is hoping to find a treasure in Amulsar, probably it didn’t take into account that those who eventually get their hands on the treasure end up being cursed for life.

The great king of Lydia Croesus probably couldn’t even imagine that he would re-appear thousands of years later in the form of a mining company hungry for gold.

So, who and why named Lydian International after Lydia? Perhaps this doesn’t even matter. Or maybe it does.

But the fact is that both the ancient kingdom and the modern mining company have something in common—a seemingly endless and persistent hunger for gold.